Featured Fungus: My Search for the Humongous Fungus (Armillaria ostoyae)

By Amanda Flaata

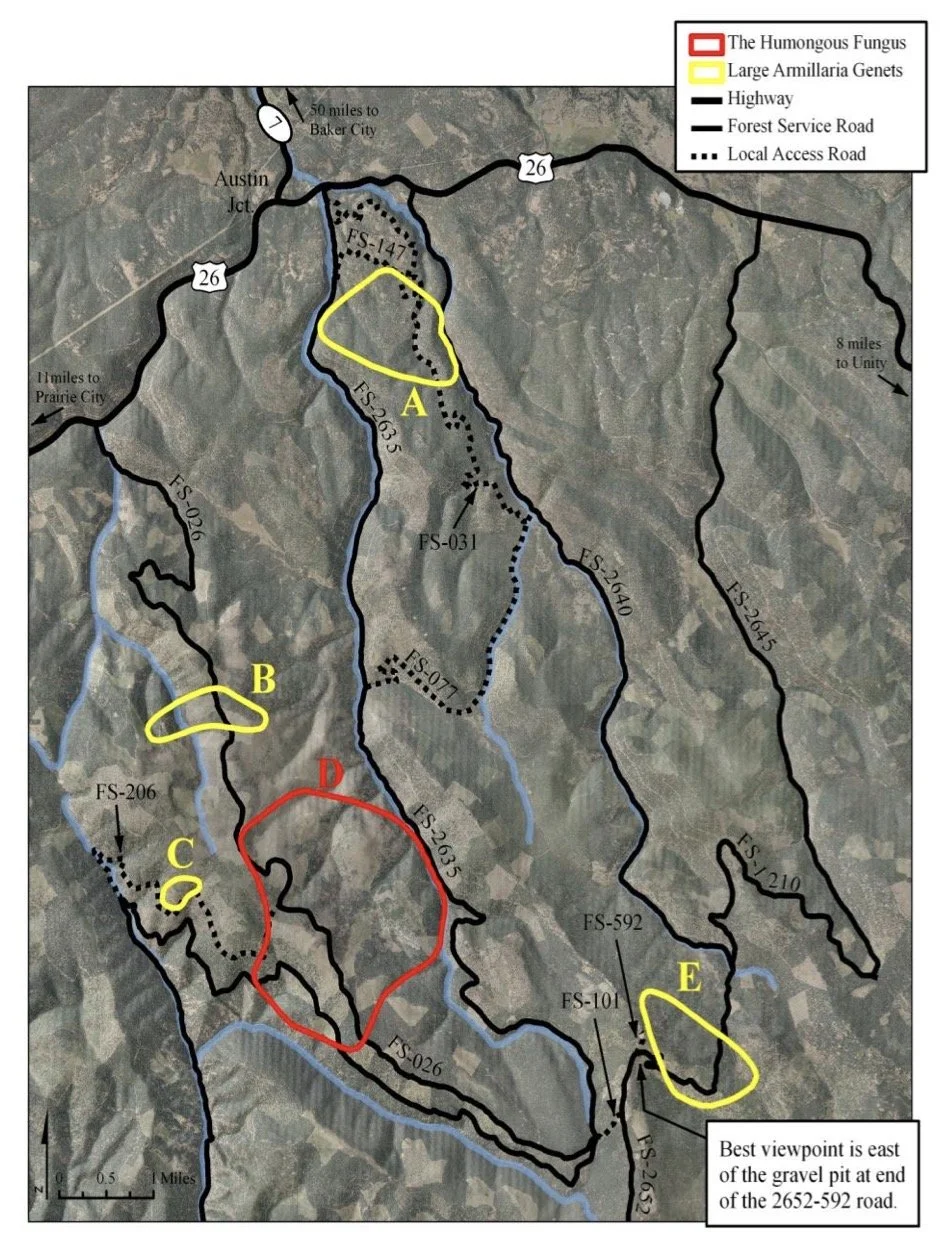

This past summer, I was presented with the opportunity to see one of the world’s largest living organisms [1], the so-called Humongous Fungus—a massive colony of Armillaria ostoyae believed to be thousands of years old and around four square miles in area—in the Blue Mountains of eastern Oregon (map 1). This was an opportunity I readily pursued, but not without its challenges.

Map 1: Map showing the location of the Humongous Fungus in the Blue Mountains of eastern Oregon

Our family was traveling by car east across the state of Oregon and decided, in the evening and on a whim, to seek out the Humongous Fungus, located in the Malheur National Forest. After an extensive conversation with the U.S. Forest Service in Prairie City, Oregon, we were advised to look for the fungus in the Reynolds Creek area, a tract of forest requiring travel on a remote service road. We proceeded, finding ourselves alone in the middle of a mixed conifer forest, slowly traveling on a road with increasingly large, sharp rocks. Even though we were only a few miles from the Humongous Fungus, we decided to call it quits, due to the time, terrain, and our inadequate vehicle (photo 1). All was not lost, however, in stopping short of reaching our destination. On the contrary, it afforded us the opportunity to explore the surrounding forest in search of evidence of Armillaria ostoyae’s reach.

Photo 1: Our parked car in the Malheur National Forest

The road divided the area into two distinct sections of mixed conifer, mainly pine and fir, forest: north of the road was a steep upward slope marked by an open area of dead and decaying trees; south of the road was a steep downward slope that led to a stream. The first thing I noticed upon exiting the car was the northern slope; there was a prominent patch of dead and dying grand fir (Abies grandis) and lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) trees, suggesting that it was a possible root disease center of Armillaria ostoyae (photos 2-3). As it was early August and not the time of year when the fungus’ fruiting bodies appear (honey fungus pops up in the fall after the first rain of the season), I knew I had to investigate dead or dying trees and woody debris for signs of infection—namely black, cord-like rhizomorphs on the exterior of root systems and under bark, and mycelial fans under the bark of live-infected trees. While I did not find any rhizomorphs, I did find evidence of mycelial fans—i.e. soft, white layers of fungal tissue that resemble latex paint with fan-like patterning—beneath the bark of grand fir trees (photos 4-5).

We then headed into the forest on the southern slope. Lured by the sound of water, we made our way to a mossy stream 200 feet from the road. Surrounding both sides of this stream were moist, needle covered areas rich in mushrooms, a surprise find given how dry the Pacific Northwest is in the summer. With the exception of Lycoperdon perlatum, a common species in Iowa, we found a variety of unfamiliar species that were at home in the Pacific Northwest, including Inocybe lacera, Inocybe lanuginosa, Xeromphalina cauticinalis, Hygrophorus chrysodon, Suillus clintonianus, Suillus ochraceoroseus, Suillus elbensis, Gomphidius subroseus (photo 6), Suillus tomentosus, Cortinarius thiersii, as well as Amanita and Russula species [2]. This section was noticeably healthier than the northern slope, but still marked by individual diseased trees, sparse foliage, and the yellowing crowns of conifers, which may indicate live infection by Armillaria ostoyae (photos 7-8). Although not part of one of the fungus’ five large clonal networks in the Malheur National Forest, like the Humongous Fungus, the area we explored clearly showed evidence of Armillaria ostoyae’s presence in actively colonizing and decaying the tissue of susceptible trees.

Photo 6: Gomphidius subroseus

The Humongous Fungus is actually the largest of five separate genets (i.e. colonies of fungi from a single genetic source) of Armillaria ostoyae in the Malheur National Forest (map 2). Armillaria ostoyae, commonly known as honey fungus, is notoriously pathogenic; its extensive hidden network of mycelium parasitizes and decays the roots of living conifer trees, eventually spreading to the root collar and base of the tree, killing it by interfering with the absorption of water and nutrients. In addition, the fungus acts as a saprobe, slowly feeding on dead organic material, with the ability to survive in buried wood, like stumps and roots, for decades. Especially in its role as a facultative parasite (an organism that may resort to parasitic activity, but is not dependent on a host for its life cycle), Armillaria ostoyae has significant impacts on forest ecology. Genet D (the Humongous Fungus) is estimated to be around four square miles in area, weigh up to 35,000 tons, and, based on its size and rate of expansion (a rate of 1-3 feet per year in all directions), be between 2400 and 8650 years old, making it one of the oldest and largest organisms on earth (Ferguson et al. 2003, Schmitt and Tatum 2008).

Map 2: Genet D (the Humongous Fungus) in red, surrounded by smaller colonies (Genets A, B, C, and E). Credit: U.S. Forest Service, image in public domain

Armillaria ostoyae’s capability for aggressive expansion is based on a combination of unique genetic features and the circumstances of forest management. Distinctive among fungi are Armillaria’s black, cord-like structures called rhizomorphs—densely packed hyphae (thread-like tubes) with a protective outer melanized layer that branch out from the main fungal body or mycelium (photo 9). These highly resilient rhizomorphs are able to seek out and transport food at great distances in the soil, even in challenging, nutrient-poor areas, or along roots, allowing Armillaria ostoyae colonies to spread far and wide (Volk 2002, Porter et al. 2022). It is predominantly through the fungus’ mycelium and rhizomorphs, not through its fruiting bodies that spread spores in the fall (photo 10) [3], that the fungus is able to infect large swaths of forest (Warrall 2025) (see GIF).

Photo 9: Armillaria rhizomorphs (photo taken in Iowa)

Photo 10: Armillaria ostoyae. Credit: Pearsall, Peter/USFWS, image in public domain

Armillaria root disease. Credit: Warrall 2025

Remarkably, in sequencing the genome of Armillaria ostoyae, Sipos et al. found significant genome expansion in areas related to the fungus’ pathogenic role, such as rhizomorph development, and the production of enzymes that break down the cellular walls of plants (i.e. lignocellulose). Also discovered were duplicated genes that allow the fungus to evade a tree’s defenses by reabsorbing chemical signals sent by the tree in the soil; the fungus is thereby able to perform a stealth attack on the tree and beat any fungal and/or bacterial competition (Sipos et al. 2017).

To compound matters, the Malheur National Forest provides the perfect environment for Armillaria ostoyae to spread. Like many western forests, this forest is well-stocked with highly susceptible trees, most notably the grand fir [4], which spread as a result of a history of fire suppression and support for the timber industry (Schmitt and Tatum 2008, Hogan 2022, Filip 2024).

The history of the Humongous Fungus is an interesting one. Genet D in the Malheur National Forest of Oregon represents the largest of several massive clonal Armillaria networks found in other areas of the United States, such as Michigan, southwestern Washington, and Colorado. In fact, the first humongous fungus was discovered in 1992 outside of Crystal Falls, Michigan and comprised a different species of honey fungus—Armillaria gallica (then called Armillaria bulbosa)—that was attacking red pine trees (photo 11); it was estimated to be 1500 years old, weigh 100 tons, and span 37 acres and was discovered using new molecular genetic techniques. After “baiting” the fungus with small pieces of wood, biologists collected and paired fungal samples in petri dishes to see if their hyphae fused together—an indication that they were part of the same genetic individual (Smith et al. 1992, Volk 2002, Casselman 2007). This was a watershed moment in mycology and biology—i.e. thinking about what constitutes an individual organism and recognizing the hidden, massive biomass potential of fungi. The discovery of Genet D—the Humongous Fungus—and other genets of Armillaria ostoyae in the Malheur National Forest in 1998 utilized such genetic testing with the addition of newer technology, such as DNA fingerprinting, to map the fungus’ expanse (Ferguson et al. 2003).

Photo 11: Armillaria gallica (photo taken in Iowa)

While Armillaria ostoyae has not (yet), to my knowledge, been documented in Iowa, it has been documented in neighboring states, especially those up north like Minnesota and Wisconsin, where conifer forests and hardwoods within conifer forests, like aspen and birch, are more plentiful [5]. Here in Iowa, other Armillaria species are abundant including Desarmillaria caespitosa (ringless honey fungus), the Armillaria mellea group (honey fungus), and Armillaria gallica (bulbous honey fungus) (photo 11), the species making up the original humungous fungus in Crystal Falls, Michigan. All honey mushrooms are edible when fully cooked and characterized by their honey yellow-brown color, white spore print, and attached or decurrent gills, with most species having rings (annuli). Our understanding of Armillaria in Iowa, however, is far from complete; greater genetic testing and research would expand our understanding of the genus. Given Armillaria’s capabilities of forming large, mobile clonal networks, we may very well have our own Humongous Fungus waiting below the surface.

Photos by Amanda Flaata, unless otherwise indicated

References

Casselman, A. 2007. Strange but True: The Largest Organism on Earth is a Fungus. Scientific American (October 4, 2007).

DeWoody, J. et al. 2008. “Pando” Lives: Molecular Genetic Evidence of a Giant Aspen Clone in Central Utah. Western North American Naturalist, 68 (4): 493–497.

Edgeloe, J. et al. 2022. Extensive polyploid clonality was a successful strategy for seagrass to expand into a newly submerged environment. Proc Biol Sci 1 June 2022: 289 (1976): 20220538.

Ferguson, B.A. et al. 2003. Coarse-scale population structure of pathogenic Armillaria species in a mixed-conifer forest in the Blue Mountains of northeast Oregon. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 33: 612-623.

Filip, G.M. et al. 2024. Armillaria Root Disease in Conifers of Western North America. United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Region.

Gilbert, L. 2022. Pando in Pieces: Understanding the New Breach in the World’s Largest Living Thing. Utah State University (September 19, 2022).

Hogan, C. 2022. What the World’s Largest Organism Reveals About Fires and Forest Health. Atlas Obscura, May 6, 2022 [accessed November 2025].

Kuo, M. 2023. Armillaria ostoyae. MushroomExpert.Com [accessed November 2025].

Porter, D. L. et al. 2022. The melanized layer of Armillaria ostoyae rhizomorphs: Its protective role and functions. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 125, January 2022, 104934.

Schmitt, C.L. and M.L. Tatum 2008. The Malheur National Forest: Location of the World's Largest Living Organism (The Humongous Fungus). United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Region.

Sipos G. et al. 2017. Genome expansion and lineage-specific genetic innovations in the forest pathogenic fungi Armillaria. Nature Ecology & Evolution 1: 1931-1941.

Smith, M., J. Bruhn, and J. Anderson 1992. The fungus Armillaria bulbosa is among the largest and oldest living organisms. Nature 356: 428-431.

Volk, T. J. 2002. The Humongous Fungus–Ten Years Later. Inoculum 53 (2): 4-8.

Warrall, J. 2025. Armillaria Root Disease. forestpathology.org [accessed November 2025].

Endnotes

[1] At present, the largest organism in the world by area goes to a clonal colony or genet of seagrass (Posidonia australis) in Australia that spans 112 miles and is around 4,500 years old. The largest organism the world by mass goes to Pando, a genet of male quaking aspens (Populus tremuloides) in Utah, estimated to weigh 6000 tons, although it is now diminishing. The Humongous Fungus is certainly one of the largest and oldest organisms on earth, but, unlike the other organisms, largely hidden from view. Interestingly enough, it holds the record for the largest bioluminescent organism.

[2] I found 26 specimens of fungi and lichen in this area of the Malheur National Forest; all observations were recorded in iNaturalist.

[3] Armillaria ostoyae mushrooms grow in clusters at the base of infected trees. They have orangish brown to pinkish brown caps with brown scales, finely hairy stems with a whitish ring, yellow basal mycelium, whitish gills beginning to run down the stem, and a white spore print (Kuo 2023).

[4] The Malheur National Forest is a mixed conifer forest, made up primarily of Douglas fir, grand fir, ponderosa pine, lodgepole pine, and western larch. While Douglas fir and grand fir are highly susceptible to Armillaria root disease, lodgepole pine is considered only moderately susceptible. Ponderosa pine and western larch are mostly disease tolerant (Ferguson et al. 2003).

[5] See this iNaturalist observation for a DNA sequenced specimen of Armillaria ostoyae in Minnesota.